Amsterdam’s vision of becoming a sustainable city

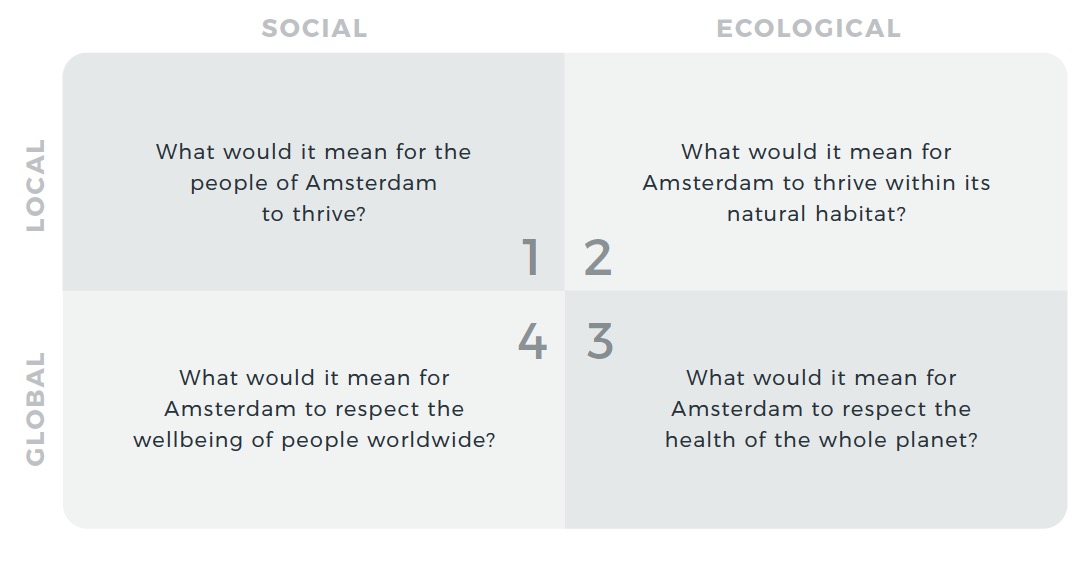

Like many other cities around the world, Amsterdam is suffering from a housing affordability crisis and wants to form a response to the climate and ecological crises. That is, Amsterdam embraced the ambition to become a city that is home to thriving people in a thriving place, while respecting the well-being of all people and the health of the whole planet.

Amsterdam City Doughnut, by Kate Raworth

Amsterdam City Doughnut, by Kate Raworth

Formulating this ambition, Amsterdam was inspired by the economist Kate Raworth and her Doughnut model for the economy. This model visualises the ideal economy as doughnut-shaped, operating between two circles: the economy of the 21st century should meet the needs of all people (the ‘social foundation’ – the inner circle) within the means of the planet (the ‘ecological ceiling’ – the outer circle).

As legal scholars with a keen interest in the role of law in the transition towards a sustainable future, we have been fascinated by two small bottom-up initiatives in and around Amsterdam: the Community Land Trust in Amsterdam South-East and the so-called Zoöp. In a recent paper, we ask how these initiatives can help the city of Amsterdam to meet its ambition to transition to a doughnut-proof economy.

The Community Land Trust in Amsterdam South-East rethinks property

In traditional area development processes, urban sites are usually maximised for economic return. But property rights can take many shapes and forms, and they might just as well be used to protect collective use rights and sustainable practices.

In the neighbourhood the Bijlmer in Amsterdam South-East, a community of more than 180 local residents are now actively working on project plans and neighbourhood development. They are inspired by the Community Land Trust (CLT) model, which finds its origins in the US from 1969 onwards. Central to the CLT are: self-organisation, shared ownership and real estate management and operation. The Bijlmer community hopes to attain land to develop the neighbourhood, based on five guiding principles:

- affordability in the present, for current residents from low- and middle-income population group;

- affordability in the future by making speculation with housing or rapid rent increases impossible;

- connectedness with the neighbourhood through permanent decision-making power of local residents over developments in the vicinity of their homes and neighbourhood facilities;

- stimulating self-reliance and providing opportunities for the socioeconomic emancipation of residents from the neighbourhood, by having them take charge of the elaboration and organization of the projects; and

- combining the development of the CLT model with circular area development.

The municipality of Amsterdam has set out in its 2050 vision statement that more space will be granted to housing and energy cooperatives and other forms of collective self-management of the living environment. However, currently the community is still waiting for the municipality to set out a tender for a plot of land in their area on which they can develop their vision of sustainable and affordable neighbourhood development, which tender has been postponed several times, to the community’s dismay.

The Zoöp model rethinks representation

The Zoöp model of the Nieuwe Instituut

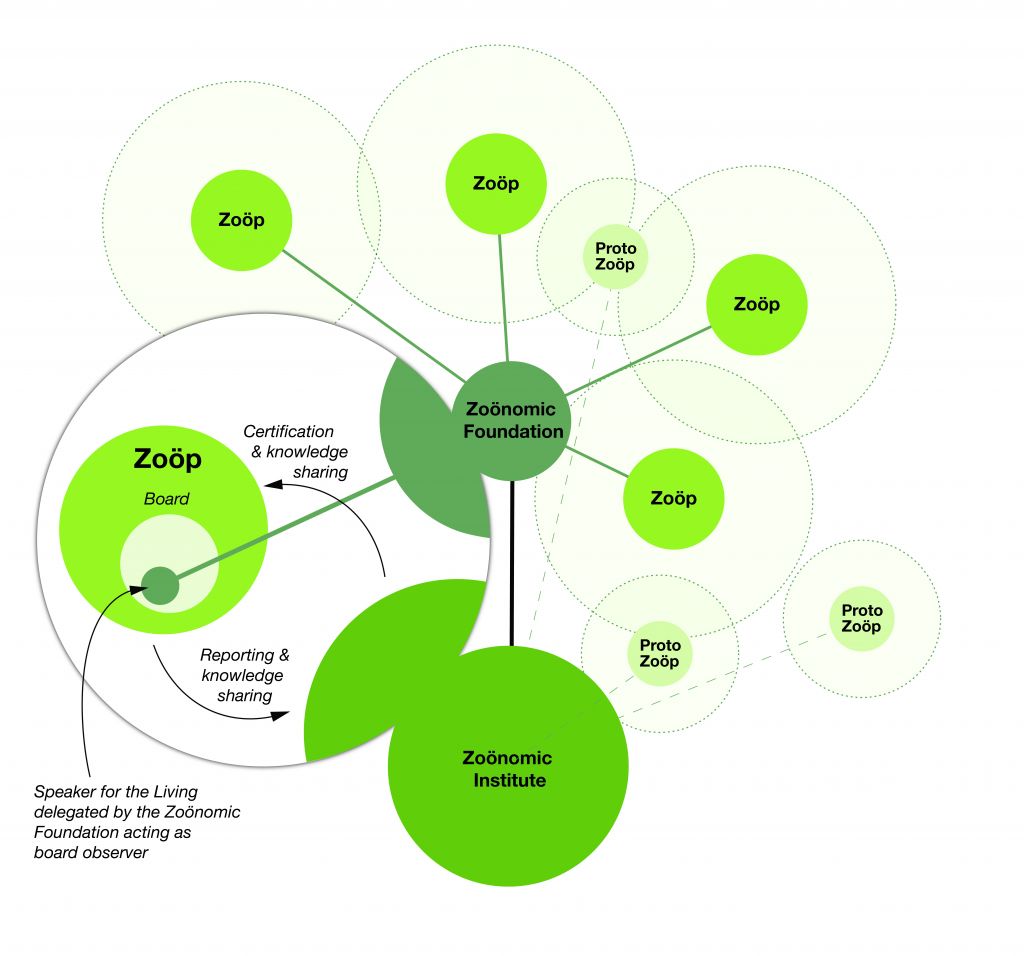

In most organisations as we know them, only humans have a voice. Also in Amsterdam, it is humans who are represented in municipal politics and in the companies that do business in the city. The Zoöp model rethinks representation: it allows all kinds of organisations to also represent nonhumans like animals, plants, and ecosystems. Zoöp stands for cooperation on the one hand, and the Greek word for life, zoe (Ζωή), on the other. The model which was launched in 2022 was developed by the Rotterdam-based museum Het Nieuwe Instituut (The New Institute), supported pro bono by lawyers from Amsterdam top firm De Brauw Blackstone Westbroek. It is heavily inspired by the global rights of nature movement.

The Zoöp model is flexible, as it can be used by both for-profit companies as well as non-profit foundations, associations or even political bodies. Moreover, it is quick: because it works with existing company and contract law, there is no need to adopt new laws. Indeed, there are already organisations inside and outside Amsterdam that adopted the Zoöp model, for example the art platform and community garden called Zone2Source, the hotel Fort Abcoude and the holiday resort Sumowala. In a rather complicated scheme, the model makes sure that there is a person on the boards of these organisations whose only task it is to represent non-humans. Nonhumans are not (only) on the menu; they are at the table in the zoöps.

There is a so-called Zoönomic Foundation, that employs ‘speakers for the living’: human experts in regeneration who can voice the nonhuman interests in the executive board of the organisation that wants to be a zoöp. To become a zoöp, an organisation must also subscribe to a ‘Zoöp Manifesto’ and make it easily accessible on its website. Once these conditions are met, a Zoönomic Institute will license the organisation as a zoöp. The newly established zoöp commits to carry out a baseline assessment, mapping the ecological system within its domain. Thereafter, the zoöp sets out yearly goals for ecological regeneration. In this way, the zoöp ensures to operate in harmony with nature.

CLT and Zoöp help Amsterdam become doughnut-proof

Can the CLT and Zoöp models enable cities to meet the needs of all people within the means of the planet? Both models make important contributions. Both the CLT and Zoöp models empower a certain underprivileged and disadvantaged stakeholder group. The CLT empowers local people, whereas the Zoöp model empowers local ecology. However, neither of the initiatives does everything at once: take good care of local people and people elsewhere and of the local environment and the planet. Still, it is Amsterdam’s ambition to care for all four.

Hence, we believe that there is room for cross-fertilization between the CLT and Zoöp models. The Zoöp model can lend its expertise to build in representation for the local natural habitat and the planet in the governance design of the CLT. The CLT’s expertise on the use of ownership to nurture a sense of stewardship for inclusive and empowered local communities can inspire the designers of the Zoöp model to maximize its potential for social inclusion. Moreover, both models would benefit from exploring how people elsewhere could be represented in their governance designs, inspired by the way in which zoöps enable representation of voiceless nonhuman actors already now.

The CLT and Zoöp models demonstrate that the legal modules of property and representation can be rethought such that the legal system can better accommodate an economic system in which neither planetary boundaries nor social foundations are transgressed. Importantly, they are able to do so by utilizing existing legal tools of company law, corporate governance and contract law without having to wait for governmental institutions to adopt legal reform.

Interested to read more? The full text of our paper is available open access: www.erasmuslawreview.nl/tijdschrift/ELR/2022/3%20(incomplete)/ELR-D-22-00036