Over the past year and a half, Professor at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, Maja Janmyr, has worked together with a team of writers, illustrators and designers to create the research comic "Cardboard Camp: Stories of Sudanese Refugees in Lebanon". The comic is based on Janmyr's research on refugee protection in Lebanon as part of the REF-ARAB project, funded by the Norwegian Research Council.

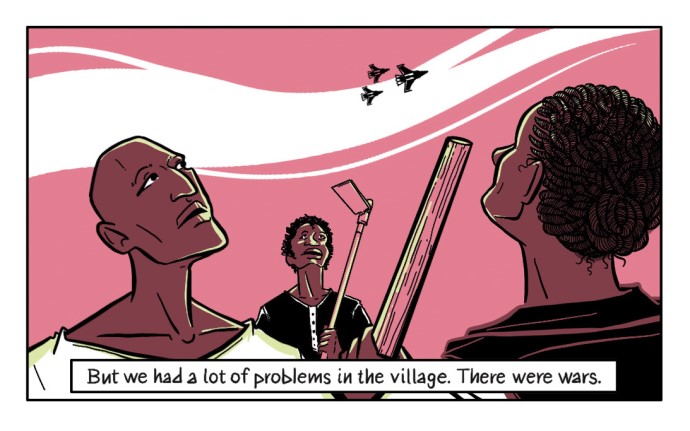

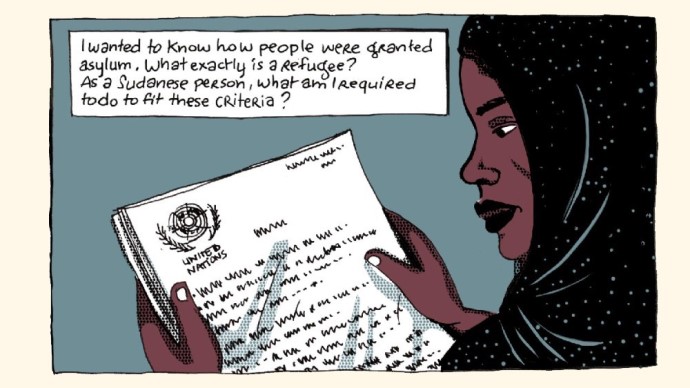

Cardboard Camp largely revolves around a protest camp that was set up outside the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, in Beirut.

– While refugees are not really expected to be politically vocal during their exile, they have, across the globe, sought to challenge existing power structures. In Beirut, Sudanese protection seekers have not remained silent and have loudly pushed for agendas defined by, and for, themselves, Janmyr says.

Alternative knowledge production

Traditional academic research dissemination, such as journal articles and conference papers, is sometimes criticized for being inaccessible for the wider public. For Janmyr, the Cardboard Camp project has opened her eyes to the potentials of visual storytelling in research:

– Visual storytelling offers an alternative knowledge production as it is another way of approaching and apprehending the world. As such, it challenges the ivory tower of academic knowledge production, Janmyr says.

Giving back to the research participants

The graphic novel was first launched in Beirut with a festive event that brought together several members of the Sudanese community in Beirut. Janmyr says it was important for her to make the research accessible to the Sudanese community:

– For me, the visual storytelling experience allowed me to communicate my research findings back to my research participants in a format that is more accessible and interesting to them. The overwhelming response at our launch event in Beirut certainly validated this approach, Janmyr shares.

Research on emotionally heavy topics

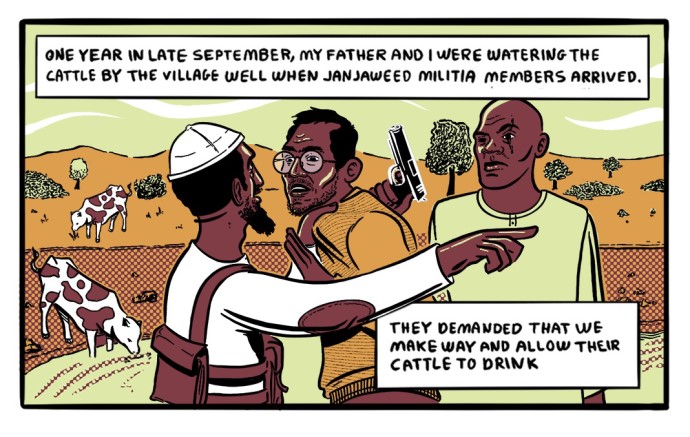

While the characters and events in the comic are entirely fictional, the depictions of life as a refugee protester draw on research carried out at the UNHCR sit-ins in Beirut over the past few years.

– Among other things, my research has highlighted how the situation of Sudanese and other African refugees is overshadowed by humanitarian responses focusing on refugee groups considered to be of greater political interest, Janmyr explains.

Janmyr highlights that visual storytelling can be an useful tool for communicating research on heavy topics:

– Graphic novels can build empathy very quickly and may even allow us to study more closely difficult topics and events that otherwise would be too overwhelming to grasp. At an early stage I wrongly assumed that comics and cartoons created a distance to a topic, but after having gone through this process I find that the graphic distillation almost makes it stronger, she says.

– Through this medium, we can explore emotionally hard research topics that standard research dissemination cannot quite grasp, Janmyr says.

A steep learning curve

The Cardboard Camp project was Janmyr's first hands-on experience with visual storytelling. While she describes the learning curve as steep, she was able to draw on the experience of a team of creatives:

– Everything started with my co-writer Yazan al-Saadi and I working mostly over Zoom and sometimes together in Beirut to write the actual script of the comic. To a large extent we used dialogue that emerged from my interviews or from other material such as video recordings made by my informants themselves, Janmyr tells.

Janmyr and al-Saadi worked on the script for about 6 months before involving four illustrators. In total, the process took 1,5 years and involved about 10 persons.

– It certainly ballooned into a bigger project than I ever could have imagined initially, and I won't deny that the process has been both time consuming and costly. I’ve been very privileged to have both the time and external funds to be able to embark on this journey. I’ve also been lucky to have access to such a stellar network of creatives, without whom this would certainly not have been possible, Janmyr admits.

Cardboard Camp is available to read and to download for free in English and in Arabic at cardboardcamp.net.